|

Listen to this article here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Haitian Revolution was a series of conflicts between 1791 and 1804 among enslaved Haitians, colonists, the armies of the British and French colonizers, and a number of other parties.

The Haitian people ultimately won independence from France and thereby became the first country to be founded by former enslaved Africans.

Saint-Domingue in the late 18th century thrived as the wealthiest colony in the Americas. Its sugar, coffee, indigo and cotton plantations minted money, fueled by a vast enslaved labor force.

It occupied the western third of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, while the Spanish had colonized the eastern side, called Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic).

Every story needs a hero

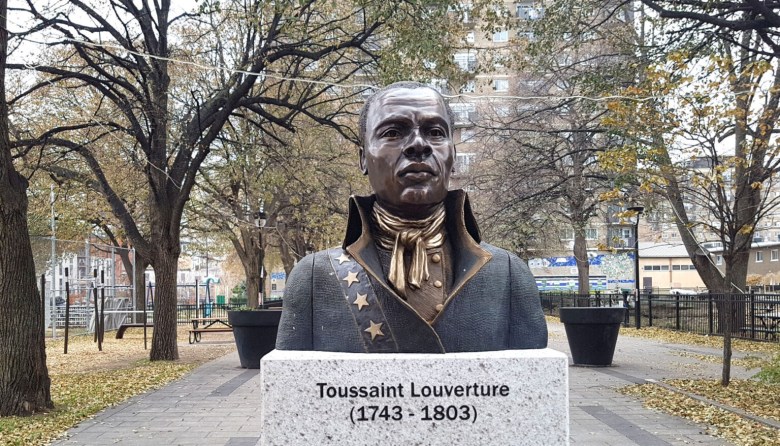

Toussaint Louverture was born enslaved on a sugar plantation on Saint-Domingue sometime in the early seventeen-forties.

Louverture, according to the scholar Sudhir Hazareesingh, was “the first Black superhero of the modern age.”

As the island’s enslaved workers organized to burn plantations and kill many owners, Toussaint initially laid low at the revolt’s onset. Having been free for some 15 years, he farmed his own plot of land in the north of the island, while continuing to oversee his former owner’s plantation.

Eventually, wielding knowledge of African and Creole medicinal techniques, he entered the war as a physician, and quickly distinguished himself as a canny tactician and a cunning, charismatic leader.

He was emancipated in adulthood and, at about fifty, led the most important slave revolt in history.

Toussaint was battle-tested and approved

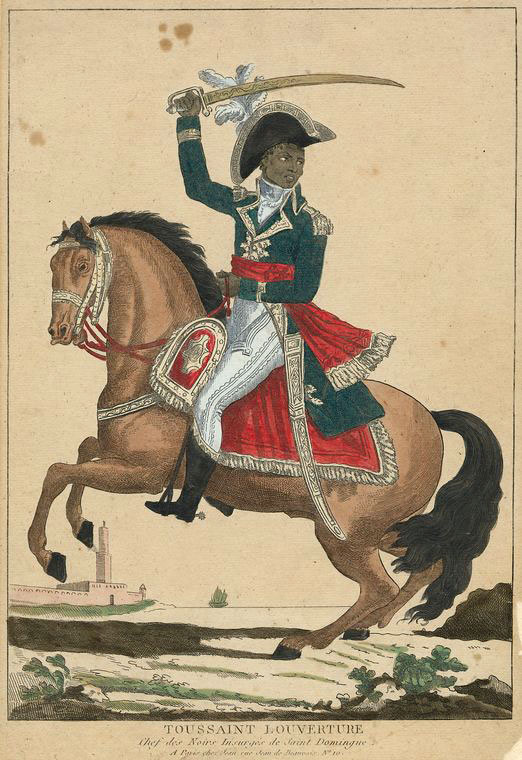

Next, Toussaint united the island’s Black and mixed-race populations under his military command; he outmaneuvered three successive French commissioners; he defeated the British; he overpowered the Spanish, and he was wounded seventeen times in battle after having lost most of his front teeth to a cannonball explosion.

According to History, “Toussaint led charges into battle, and survived numerous brushes with death, lending him a supernatural aura that he cultivated to enrapture followers and enemies alike.”

His reputation was one of grandeur. One French official in Saint Domingue credited Toussaint’s ability to be in several places at once to his vitality and unmatched understanding of the terrain. And after Napoleon Bonaparte sent 20,000 French troops in 1802 to regain control of Saint-Domingue, a secretary in the expedition described Toussaint as like a tiger: visible where he wasn’t and invisible where he was.

Bonaparte first sent twenty thousand men to overthrow him, reinstating slavery in the French colonies, in 1802. In response, Louverture torched the capital city, “so that those who come to re-enslave us always have before their eyes the image of hell they deserve.”

As a general, Toussaint led his forces to victory over the planter class—and thousands of invading French troops. But that was only the start. Navigating the complex, ever-shifting politics of dueling colonial powers, he successfully repelled the aggressions of Europe’s mightiest nations (France, Spain and England), using diplomatic wizardry to cannily play them off one other.

Toussaint would not live to see his country’s eventual independence. Captured during Napoleon’s 1802 expedition to subdue the colony, he was transported to a French jail, where he died a year later.

While it was his radical deputy, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who would outlast the French assault and declare Haiti’s independence as the world’s first Black republic in 1804, it is Toussaint’s leadership that manifested Haiti’s birth.

The emblem of the Haitian Nation shall be a flag with the following description:

A) Two (2) equal-sized horizontal bands: a blue one on top and a red one underneath;

B) The coat of arms of the Republic shall be placed in the center on a white square;

C) The coat of arms of the Republic are: a Palmette surmounted by the liberty cap, and under the palms a trophy with the legend: In Union there is Strength (L’Union Fait la Force).

Toussaint Louverture led The Haitian Revolution with his mind first — sword second.

Toussaint was aware of his regiment’s lack of training, but he was also aware of France’s desperate position in the face of Spanish and British hostility. So when it suited his needs, he joined forces with France’s enemies.

Feigning outrage at the execution of King Louis XVI in 1793, he made an alliance with neighboring Santo Domingo, taking command of a Spanish auxiliary force to reclaim a swath of Saint-Domingue territory.

He refused to negotiate with French commissioners until 1794, when France formally abolished slavery in its territories.

Toussaint then rejoined the French forces, beat back the Spanish and began his sustained campaign against the British.

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

His army ousted British forces in 1798, causing them to lose more than 15,000 men and 10 million pounds in the process.

According to The New Yorker, The Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot argued that the Haitian Revolution has been “silenced” in part because it was “unthinkable even as it happened”: a White army, once thought to be unmatched by Europeans and Americans, as well as of observers in Saint-Domingue, defeated and overmatched by the military triumph and political birth of a Black nation.

Haiti was set up to fail after winning the war

In 1825, France imposed a crippling indemnity on Haiti, under threat of war, forcing the nation to borrow money from a French bank at extortionate rates in order to compensate former slaveholders.

The French recognized Haiti’s independence but in return demanded a hefty indemnity of 100 million francs, approximately $21 billion (USD) today. It took Haitians more than a century to pay off the debt to its former slave owners and lenders, including the City Bank of New York, experts who spoke with ABC News said.

“By forcing Haiti to pay for its freedom, France essentially ensured that the Haitian people would continue to suffer the economic effects of slavery for generations to come,” said Marlene Daut, a professor at University of Virginia specializing in pre-20th century French colonial literary and historical studies.

The Haitian Revolution and the subsequent declaration of independence caused an economic whiplash that has left parts of Haiti mired in abject poverty, political upheaval, unrelenting gang violence, and in dire straits after earthquakes have crumbled much of its infrastructure.

The country’s GDP remains extremely low at $1,149.50 per capita and nearly 60% of Haitians currently live in poverty.

Among other factors, today, Haiti exists among the poorest nations in the world, and it is the single poorest country in the western hemisphere.